\[\begin{array}{cccc} & \bm {f(n)} & \bm {c} & \bm {f_c^*(n)} \\ \hline \bm {a.} & n - 1 & 0 & \textcolor{blue}{\Theta(n) } \\ \bm {b.} & \lg n & 1 & \textcolor{blue}{\Theta(\lg^* n) } \\ \bm {c.} & n/2 & 1 & \textcolor{blue}{\Theta(\lg n)} \\ \bm {d.} & n/2 & 2 & \textcolor{blue}{\Theta(\lg n)} \\ \bm {e.} & \sqrt n & 2 & \textcolor{blue}{\Theta(\lg \lg n)} \\ \bm {f.} & \sqrt n & 1 & \text{\textcolor{blue}{NA}} \\ \bm {g.} & n^{1/3} & 2 & \textcolor{blue}{\Theta(\log_3 \lg n)} \\ \bm {h.} & n / \lg n & 2 & \textcolor{blue}{\omega(\lg \lg n), o(\lg n)} \end{array}\]Iterated Functions

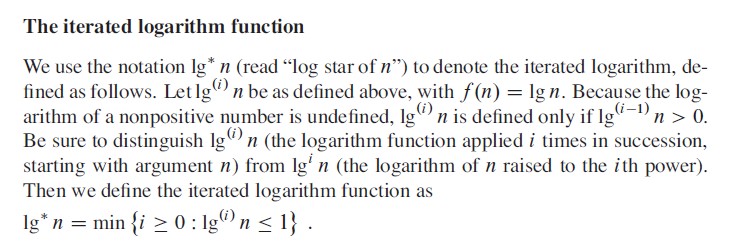

We can apply the iteration operator \(^*\) used in the \(\lg^*\) function to any monotonically increasing function \(f(n)\) over the reals. For a given constant \(c \in \R\), we define the iterated function \(f_c^*\) by

\(f_c^*(n) = \min\{ i \geq 0 : f^{(i)}(n) \leq c \}\),

which need not be well defined in all cases. In other words, the quantity \(f_c^*(n)\) is the number of iterated applications of the function \(f\) required to reduce its argument down to \(c\) or less.

For each of the following functions \(f(n)\) and constants \(c\), give as tight a bound as possible on \(f_c^*(n)\).

What sorcery is this?

As I have mentioned in the foreword, the goal of these solutions is not just providing the answer without engaging in the discussions required to understand the process.

I’ll take few examples for now to explain how to find the tight bounds. For others, I’ll revisit later or add based on comments.

Readers are encouraged to provide their own solutions as always.

A. \(\bm {f(n) = n - 1}\)

As \(c = 0\), we are looking for how many times \(f(n) = n - 1\) has to be applied on \(n\), to make \(f(n) \leq 0\).

\[\begin{array}{cccc} \textbf {Iteration} & \bm {f(n)} \\ \hline 1 & n - 1 \\ 2 & n - 2 \\ 3 & n - 3 \\ \vdots & \vdots \\ n & n - n = 0 \end{array}\]So, \(f_c^*(n) = n\), which is \(\Theta(n)\).

B. \(\bm {f(n) = \lg n}\)

If you have read the section in the book where iterated logarithm functions is defined (page 58 in 3rd edition), you can see that this is exactly what was defined.

Since, \(c = 1\), \(f_c^*(n) = \lg^* n\), which is \(\Theta(\lg^* n)\).

CD. \(\bm {f(n) = n/2}\)

For \(c = 1\), the number of times a number \(n\) can be divided by 2, before it becomes less than or equal to 1 is \(\lg n\).

And for \(c = 2\), it’ll be \(\lg n - 1\).

Both of them are \(\Theta(\lg n)\).

EF. \(\bm {f(n) = \sqrt n}\)

\[\begin{array}{cccc} \textbf {Iteration} & \bm {f(n)} \\ \hline 1 & n^{1/2} \\ 2 & n^{1/4} \\ 3 & n^{1/8} \\ \vdots & \vdots \\ k & n^{1/2^k} \end{array}\]For \(c = 2\), we need to find \(k\) for which \(n^{1/2^k} = 2\).

\[\begin{aligned} n^{1/2^k} &= 2 \\ \lg (n^{1/2^k}) &= \lg 2 \\ \frac {\lg n} {2^k} &= 1 2^k &= \lg n \\ k &= \lg \lg n \end{aligned}\]So, \(f_c^*(n) = \lg \lg n\), which is \(\Theta(\lg \lg n)\).

However, for \(c = 1\), there is no possible finite value of \(k\) that can make \(n^{1/2^k} = 1\). It is only possible when \(k \to \infty\).